Sierra Leone Part 4: the abolition of the slave trade, and the return of the “recaptives”

[This is the final part on the history of Sierra Leone]

Just seven years after the arrival of the Maroons and twenty-five years deep into the abolitionist movement, in 1807 came the Act for the Abolition of The Slave trade and a massive, and deeply duplicitous role change for the British and their role in transatlantic slavery. Having dominated the slave trade for all of the years in living memory, almost overnight the British would recast themselves as the saviours who would stop it, all the while sleeping comfortably in their mansions built on the blood and sweat of slavery. The last part of this story is about the role Freetown would play in this enormous change.

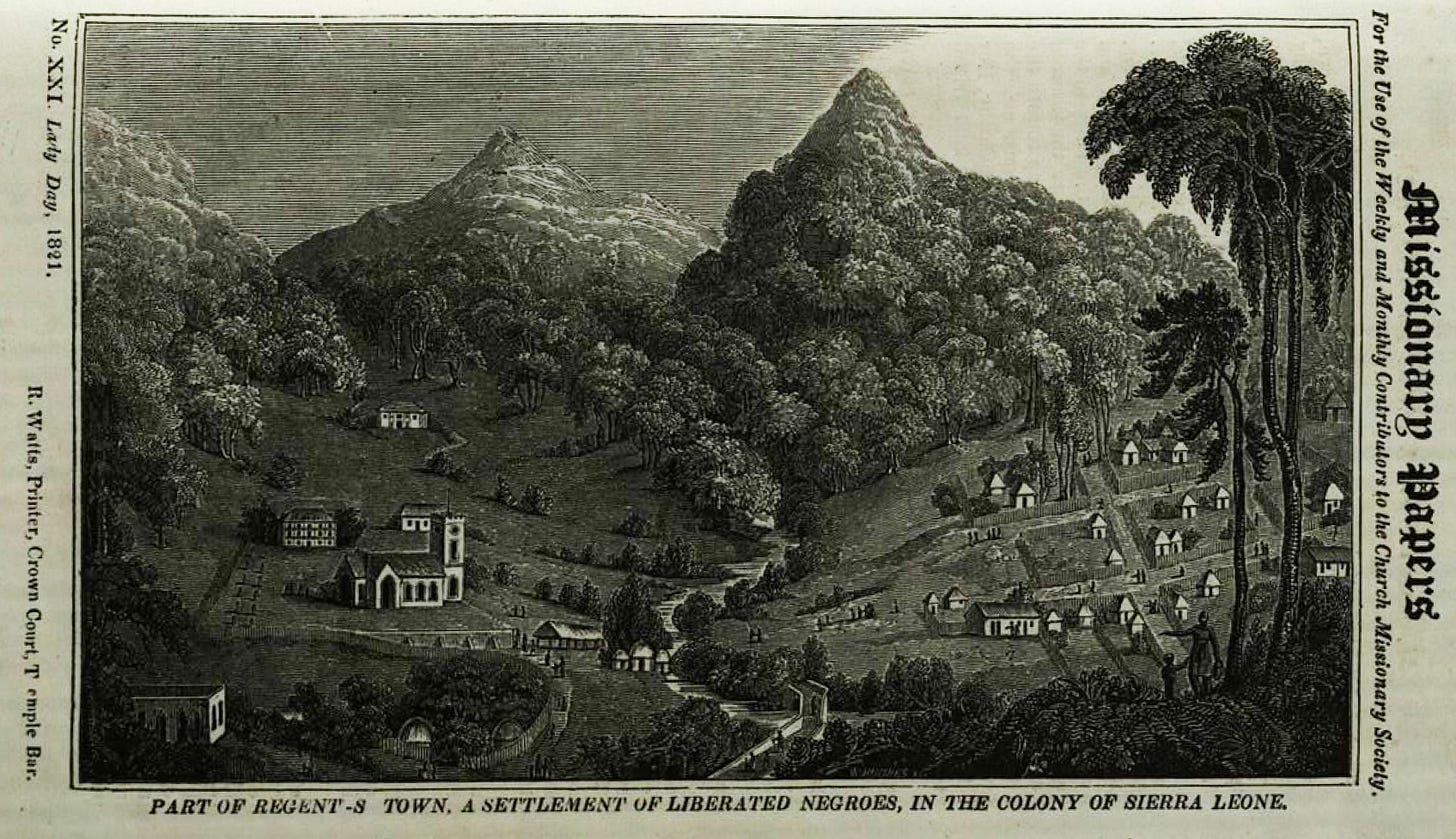

As soon as the slave trade was made illegal, the Royal Navy set up blockades at the mouths of several significant rivers on the West Coast of Africa. The idea was to block slaving ships from leaving Africa and to impose sanctions on them, and force them to release the enslaved people they were carrying. The Navy were making money for each boat they stopped, not to mention the assets seized on the boats themselves. It became a business very fast, and with it, a whole new infrastructure was needed. In 1808 the British wanted to set up a Vice Admiralty Court to process these stopped boats and felt the best place to do it was Freetown. If Freetown now had a court to process slavers, what would happen to the released slaves - the recaptives as they would be known? Recently enslaved, newly liberated Africans would make up this fourth and final wave of movement (we can’t really say immigration) towards Sierra Leone and the population of “recaptives” would rocket from 2000 in 1807 to 50,000 in 1850.

Many people on the boats which were captured before leaving Africa did not make it back to land. The Portuguese for example, when captured, would often tell the enslaved people on board that the British were going to sell them to cannibals, to try to incite them to jump overboard instead of docking, because the less enslaved people they had on board, the less likely they were to be convicted of slaving. But for those who did dock back in the deep harbour of Freetown, life would be anything but easy. Often this fourth wave of people to settle in Sierra Leone struggled enormously to integrate, housed as they were in makeshift refugee camps and speaking often no languages which were spoken in the settlement.

In the decades that followed, the extraction of enslaved people from Africa became more and more difficult but with the plantations flourishing, the demand for slaves rose drastically. Slavers began going further south on the West coast of Africa and in time the abolitionist movement realised that the only way to stop them was to abolish the institution itself. So they lost interest in Sierra Leone, it was left to its own devices, meaning that the well-meaning but misdirected energies of abolitionism would no longer be there to temper the capitalist interests at play in the colony.

In 1830, the British declared that they would begin to phase out white officialdom in the Colony, but this never fully materialised and the country developed in a manner closely yoked to Britain, developing a merchant class and a bourgeoisie by the 1860s which would include the world's first black bishop (Samuel Crowther) and a black Knight (Sir Samuel Lewis). Sierra Leone in many ways became exactly the kind of rags-to-riches story over which the Victorians (so often themselves in either rags or riches) loved to fantasize over. But as the century moved on, the British financial and colonial interests in Africa lay further along the coast (Nigeria and Ghana) and to the South (South Africa, Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe) and by the time of the Berlin Conference in 1884, Sierra Leone had become merely a small British enclave, bordering the independent Liberia and German colonised Guinea. It was no longer of key importance for the British as a territory.

In 1947, just after WWII, Atlee’s Labour cabinet was involved in making a new constitution for Sierra Leone and whilst this may have been welcomed by many Sierra Leonians, the creole population (the descendants of the first three waves of settlers) were frightened about Britain's perceived stepping away, petitioning them not to in 1948 and then again in 1950. The 1950 petition produced this incredible document addressed to the very queen who still rules today:

“The Humble Petition of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Sierra Leone under the aegis of The Sierra Leone National Council Sheweth:

That your Majesty’s petitioners are British Subjects, and Descendants of the Settlers, Nova Scotians, Maroons and Liberated Africans for whom this Settlement was acquired in 1788, (hereafter described as The Council):

2 That The Council would humbly seize the opportunity of expressing their loyalty, devotion and attachment to Your Majesty’s person and throne;

3 That as mother of the The West African Colonies, Sierra Leone with her invaluable Atlantic Sea-Board, and with a history whose romantic nature no other Colony could surpass, has been subjected to many vicissitudes and unfortunate official measures since the earliest days of her annals….”

Of course this was not a loyalty shared by everyone in the country, maybe more of a historical oddity, a kind of Stockholm syndrome, deeply unsurprising after the Divide and Conquer rule of the British. But the desire of these descendants of the original settlers to remain a colony was undermined by the energy growing in the restless empire and by the time that independence arrived in 1961, these creoles, of whom there were around 25,000, would be outnumbered by 100 to 1.